October 6th: Our B&B had a cute breakfast bar that included a milk-foaming machine.

It rained heavily all day, so we didn’t do anything or go out, except for dinner.

October 7th: Duino is famous for many things. On September 5, 1906, Ludwig Boltzmann hanged himself here while on vacation with his wife and children. He had been in bad health, and depressed because most mainstream scientists rejected his theories. He should have stuck around; over the next few years his ideas were spectacularly vindicated. But remember, we’re talking about a time when (for example) over half of all chemists didn’t think atoms were real. Defenders of physics orthodoxy could be real assholes, just like today. He had to put up with a lot of criticism from e.g. Ernst Mach and the logical positivists.

Crudely, logical positivism says that you should not have anything in your theories that does not correspond to something you can either perceive directly or measure with instruments. No one had seen an atom, and no one had detected a single atom with an instrument; therefore, any theory talking about atoms was automatically flawed, malformed, grotesque, and entirely the wrong way to think about things.

This was the kind of pompous idiotic shit that drove Boltzmann to suicide.

Bohr and Heisenberg were logical positivists. Heisenberg’s “matrix mechanics” painstakingly avoided talking about what actually happens inside an atom. It was all like, here are the inputs, and here are the outputs, and that’s all you can ever know.

It seems sensible to discard all hope of observing hitherto unobservable quantities, such as the position and period of the electron… Instead it seems more reasonable to try to establish a theoretical quantum mechanics, analogous to classical mechanics, but in which only relations between observable quantities occur.

Werner Heisenberg, quoted in Helge Kragh, Quantum Generations: A History of Physics in the Twentieth Century (1999), p.161

Meanwhile, Schrödinger had been taking de Broglie’s theory of particle waves seriously. There must be some sort of wave mechanics that described how they behaved. At a gathering, an older physicist scoffed at the very idea. “How can you have a wave theory when you don’t have a wave equation?”

It was a reasonable objection. There’s a wave equation for how water moves, another for how sound travels through air, another for a guitar string or a wiggled slinky. You aren’t considered to understand any of those phenomena until you can write down the wave equation and solve it.

So Schrödinger tried to devise such a wave equation. He had most of the key ideas by December 1925, when he went on a ski vacation with his girlfriend. (His wife, who knew, was having an affair with mathematician Hermann Weyl at the time, and was probably happy to have him out of the house.) All the pieces finally fell into place, and he came down off of the mountain in January with the now-famous Schrödinger equation.

It was a horror to the positivists. Heisenberg wrote to Pauli, “The more I think about the physical portion of Schrödinger’s theory, the more repulsive I find it…. What Schrödinger writes about the visualizability of his theory “is probably not quite right”; in other words it’s crap.”

But it wasn’t crap. It explained everything. Spectroscopy. Atomic bonds and chemistry. Crystals, and eventually transistors and integrated circuits. Nobel prize after Nobel prize followed. The positivists had been spectacularly wrong again.

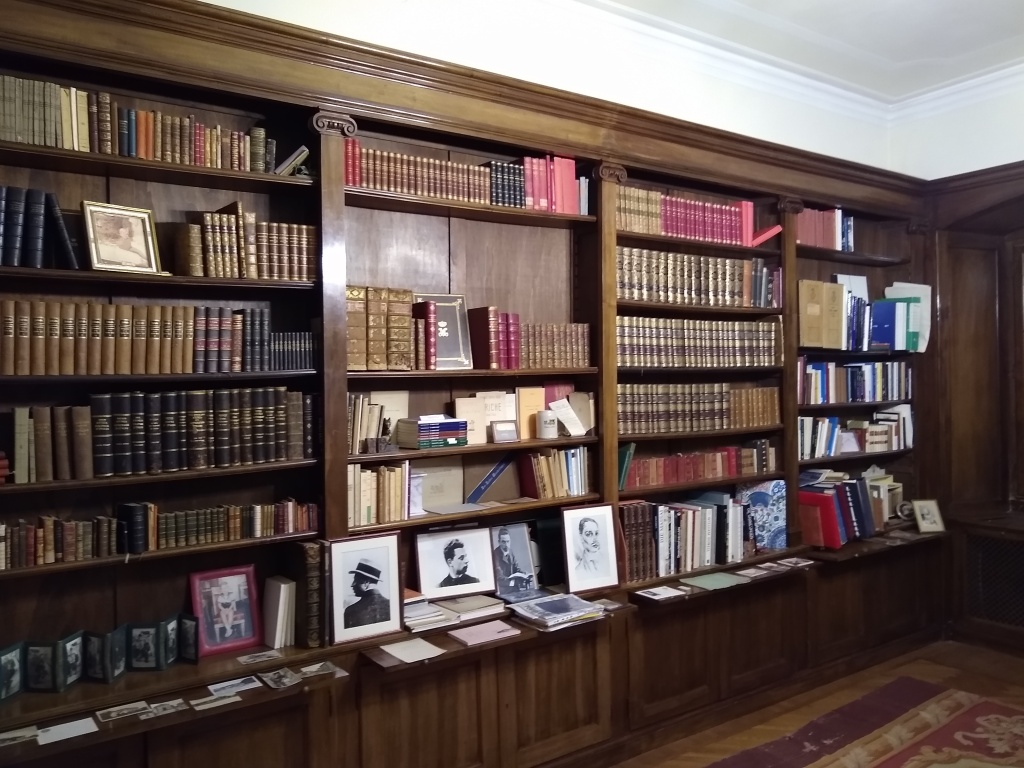

However, I didn’t come to Duino because of Schrödinger, or because of Boltzmann (whose grave-shrine is in Vienna). I came because of Rainer Maria Rilke, who lived in Castello di Duino as a guest of Princess Marie von Thurn und Taxis. The Duino Elegies were started here in 1912. Many of Rilke’s poems are dedicated “to” or “for” someone, but when he finally finished the Elegies in 1922 he called them “property of” Princess Marie.

And before I knew it, we had arrived at the holy of holies; the balcony where Rilke heard the first line of the first Elegy: Wer, wenn ich schriee, hörte mich denn aus der Engel Ordnungen? (“Who, if I screamed, would hear me among the ranks of angels?”)

At least, that’s the myth. Duino Castle was heavily damaged by bombing in WW I, and had to be rebuilt. Maybe this balcony survived, maybe it was reconstructed. And a different story says that Rilke was walking the trail along the cliffs in the background. But we desire certainty, so we say: It was here.

But there was still a lot more castle to explore.

Rilke would have been comfortable here, as the castle was luxuriously furnished.

Finally, it was time to leave the castle and embark on the “Rilke walk”.

After the hike, we headed back to our B&B, checked out, and got on the road again.

Lunch was meat grilled on a metal skewer, which came to the table sizzling hot.

Then we drove all the way to Poreč, Croatia. Dinner was less elaborate, just Croatian fast food.